resampling previous portfolio

After writing this

post, I kept thinking about the concept of "resampling", and I want to take it yet one step further.

If resampling makes sense, and I think it does, and if it can help discover an overoptimized portfolio (where

coincidentally the wins by one system compensate for the losses by another), then the process should be able to detect the huge mistakes in our previous portfolio (investors' and mine), which was intentionally optimized, because we thought that was the way to find the optimal portfolio (we even used a genetic optimizer, Palisade's RiskOptimizer).

Given that the risk of blowing out (by starting trading at any given date) doubled for my present

non-optimized portfolio on both my forward-tested and back-tested sample, I would expect that hyper-optimized portfolio to at least triple (relative to the regular chronological order of trades) after a resampling of the back-tested data. My present non-optimized portfolio went from 5% to 10% (chance of blowing out) for forward-testing and from 11.5% to 23% for back-testing. Which tells me that one way or another I did optimize it, even though not scientifically and not consciously.

Let's see what happens to this one, and if, in fact, resampling can help detect an overoptimized portfolio.

Ok, first of all,

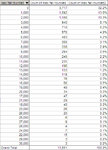

step #1, the non-relativized performance we assessed was on a daily basis, and here it is:

Code:

[B][COLOR=red]max dd $ max dd days total profit $ sharpe[/COLOR][/B]

-17,879 28 1,650,783 4.92

Step #2: while we were already trading the 160k portfolio, in August, I was asked to calculate the relativized drawdown, and the relativized performance, always day by day, and I came up with this information:

Code:

[B][COLOR=red]max dd $ max dd days total profit $ sharpe[/COLOR][/B]

-26,574 45 2,220,009 4.42

11k increase in max dd in dollars, 17 days increase in days, increase in absolute profit, and decrease in sharpe ratio.

This relativization already brings us closer to reality, with a 50% increase in max drawdown (both depth and duration) and yes an increased profit, but not enough to compensate for the increased drawdown, so the sharpe ratio gets worse, even though by not much. But even if it stayed the same, this tells us that we need a bigger capital.

Now, after relativizing drawdown, let's see

step #3: what happens if we go from a daily timeframe to a trade-by-trade timeframe? This should bring performance a bit down (the higher the timeframe, the more losses tend to be hidden by the profit of profitable systems, and viceversa), and it should bring us yet another step closer to reality.

Code:

[B][COLOR=red]max dd $ max dd days total profit $ sharpe[/COLOR][/B]

-30,253 N/A 2,220,009 N/A

Since, as expected the difference is small, I will now focus on the statistical data that I was gathering yesterday, telling us the probability of blowing out by starting at any given day with x capital (I'll analyze that differently, because, unlike my capital, the investors had a much bigger capital).

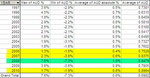

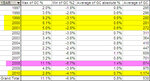

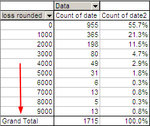

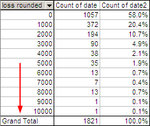

So here is step #3 again (relativized drawdown on a trade by trade basis) but with different information:

The investors were willing to risk all the profit made to date (37k) plus some more. According to this table above, the risk of blowing out, with that available buffer capital, "profit cushion", "uncle point", whatever you want to call it, is zero %. So that portfolio, which failed (or simply got unlucky: you don't have to be wrong to blow out an account) seemed on paper much much safer than what I am trading right now (relatively to the capital available). With the portfolio I am trading right now, according to backtesting, I have an 11.5% chance of blowing out. That one says zero. Go figure. I mean I already knew this, but I hadn't fully realized it. After taking that beating I went and traded what appears to be an even riskier portfolio. Even though I have a feeling that the systems are better and I am certain that my portfolio is less optimized, in that I chose the best systems, and not (via genetic and brute-force optimization) those that fitted together the best. But the statistics aren't showing yet. At all.

[...]

IMPORTANT:

Wait a minute: if the systems in the long run are correlated and by overoptimizing the portfolio I chose a combination that limits but doesn't entirely eliminate this correlation, by resampling I might even get a better result, because if there's anything my resampling does is guaranteeing there's no correlation between any of the systems. So I guess resampling is only good at detecting if I put together a bunch of systems that compensate each other, but it might yield even better results than reality when I could not manage to fit together the systems. The reality is that my optimization is better than reality, but also resampling is better than reality, because in reality systems are correlated. Let's just say that resampling is there to tell us that the systems are at least as bad as resampling, in case we got better results from the datasample available.

Let's move to

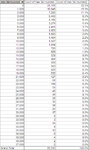

step #4, and see what resampling (randomizing the trades) does to that "160k" portfolio. If it will give us worse results, it will mean that the portfolio is less curve-fitted than random trades, thereby representing and suffering from the correlation of trades, but still more curve-fitted than what the future is like, and underestimating the correlation of trades and systems. (Or, once again, we might have gotten very unlucky).

Given that for my present portfolio the results of resampling were these:

1) back-testing: % of blowing out from 11.5 to 23%, max drawdown from 10k to 20k.

2) forward-testing: % of blowing out from 6% to 12%, max drawdown from 5k to 10k.

And, given that this 160k portfolio was extensively overoptimized, I would expect the 30k drawdown to more than double, at least to triple. And I would expect the % of blowing out to go from zero % to 20%. Plus of course, as mentioned and explained several times there are many reasons (soccer championship example) why the future is worse than the past (according to my estimates, from previous trading, the future is half as good), and this might explain why we stopped trading exactly at the lowest point of the drawdown, which was 48k, at the end of September (it kept going up ever since).

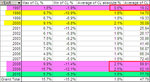

Here it is,

step #4:

The max drawdown did not triple but increased only by 30%. And the % probability of blowing out is still zero, given that we waited until 48k (pretty amazing that we stopped trading exactly on the day of the max drawdown), and that according to the resampling summary table, there are no situations where that drawdown would ever be reached, even had the trades be random.

Now the problem is two things: by optimizing the portfolio I managed to make the trades slightly better than random (just 30%), but we know that all futures are correlated, and that creating, on those correlated futures, systems that are not correlated is practically impossible. So, even this resampling, as i said before, only tells us: "hey, you can't expect your systems to do better than me" (i.e. "random trades"). But what I am saying is that even this extra step ("step #4", after #2, relativizing losses, and #3, switching the timeframe) of resampling would not have warned us as to the risks of the portfolio.

The only thing missing is that there's an

underperformance relative to the past.

So it's not only every portfolio that does better than random sampling of its back-tested trades is overoptimized (by choosing the systems that fit well together).

We also have to expect an underperformance due to:

1) the systems losing their edge because others start using them

2) the markets changing

3) the survivorship bias or a similar concept (i don't know what it's called), the championship bias. Some systems may be successful just because they got lucky and you found them by trying and trying (despite the out-of-sample methodology, some lucky ones could get through). Other systems may have won the soccer championship but that doesn't mean they'll keep winning: just because you pick the previous winner, it's not automatically the next winner. Things keep changing (I guess this is close to point #2).

For one reason or for another, that I can't explain nor understand fully, my estimate is that my systems, even without optimizing the portfolio perform 50% worse. You expect 50k of profit, and you only get 25k. You expect a drawdown of 37k and you get more, maybe 50k.

Basically, we did overoptimize the portfolio, and we did get very unlucky, but even after taking that into account, to explain the bigger drawdown, we have to recur to this concept of underperformance.

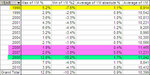

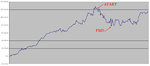

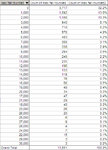

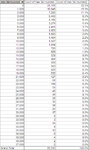

So, what happened to the famous 160k portfolio that we started trading on the 16 of August and stopped trading on the 26 of September? Here it is (this below is the forward-tested sample, which covers a different period from the back-tested sample, on which i based the study and tables until here):

And, in light of this, what are my chances of not blowing out?

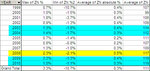

It depends how we interpret that 50% underperformance. Given that a portfolio cannot expect to have better trades than its trades randomized, we have already brought the relativized max drawdown from 10k to 20k, and the probability of blowing out (with a capital of 4k) from 11.5% to 23%.

Now we should add to that, the certainty of 50% (my estimate) underperformance. This will bring me to about 33% chance of blowing out and 66% of surviving. Also, I am counting on the fact that this time I did not choose the systems based on how well they fit together but on how good they are: I practically chose all the best systems and found out that they fit well together (I probably got rid of one or two that did not fit well, but nothing compared to the previous portfolio, where I used the palisade's RiskOptimizer software).

So, I am risking 2k, and I am going ahead with the experiment, knowing that I have on my side about 66% of probability.

Chopin Nocturne Op. 62 #2 - Rock version - YouTube

I said before, but it's important so I am just going to repeat this to myself to clarify it. Writing just as I think out loud.

A portfolio's trades cannot be uncorrelated, no matter how many futures you're trading, it's not going to be like rolling dice or flipping coins. So, if resampling the trades turns out to be worse than your back-tested results it means that your sample was lucky or that you made it lucky by choosing only specific systems. Then what counts as correct is the performance on the resampled sample.

If instead the systems turn out to do worse in the back-tested sample than in the resampled one, it means you didn't overoptimize anything, and you should trust the worse result, which the ones on your sample.

On top of all this crap (relativization of profits/losses, measuring trade by trade, resampling), you have to add an underperformance of your systems by about 50%. Only then will you have fair assessment of your future risk with that portfolio and capital.