When you click the “Buy to Open” button on your option trading platform, from whom are you buying? And does it matter? Well yes, it does matter. It can affect the price you pay for the option, to the degree that it might make the difference between a winning trade and a losing one.

The options market is made up of multiple exchanges. Each exchange hosts many options “market makers.” The market makers are broker/dealers, whose job is to buy options wholesale and sell them at retail. These dealers are always present in the market.

The market makers’ computer systems make sure that they have a bid price and an offered price in the market at all times for all the options they deal in. This is true whether any trades have taken place in each option or not.

Their presence explains why the option chain for each stock is fully populated. All the market makers are constantly transmitting their bid and ask prices to their exchanges.

The exchanges co-operate in a committee called the Option Price Reporting Authority (OPRA), which aggregates all the data and feeds it out to the public through data vendors. What we see on our option chains is the result of this aggregation and dissemination from OPRA.

This includes bids and offers from all of the option market makers, as well as from all other traders, including you. We see just one number as the “Bid” for the option and another for the “Ask.” But these are just the best (highest) bid and the best (lowest) ask price available among the many bids and asks from all the players.

All well and good as long as there are plenty of people competing for our business on whatever options we’re interested in. As long as that is true, the spread between the bid price and the ask price will be narrow. The competition from other traders will keep the market makers honest; if the market makers were to try to maintain a wide bid-ask spread, they would be undercut by the other players and that spread would narrow.

That is what happens with options that are widely traded. Below is an illustration:

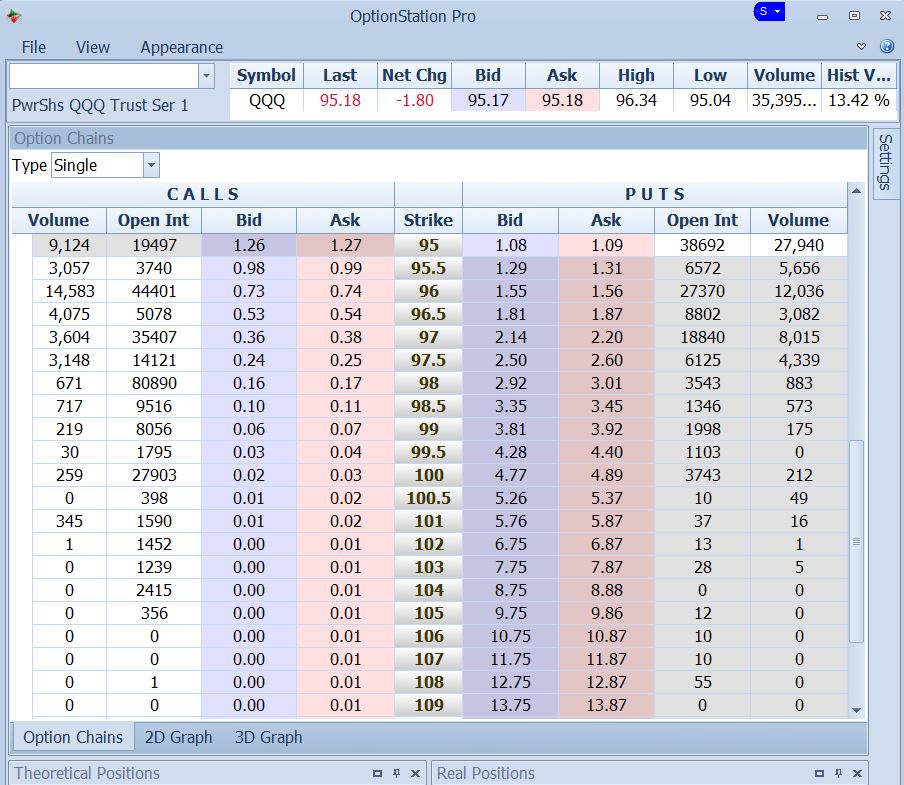

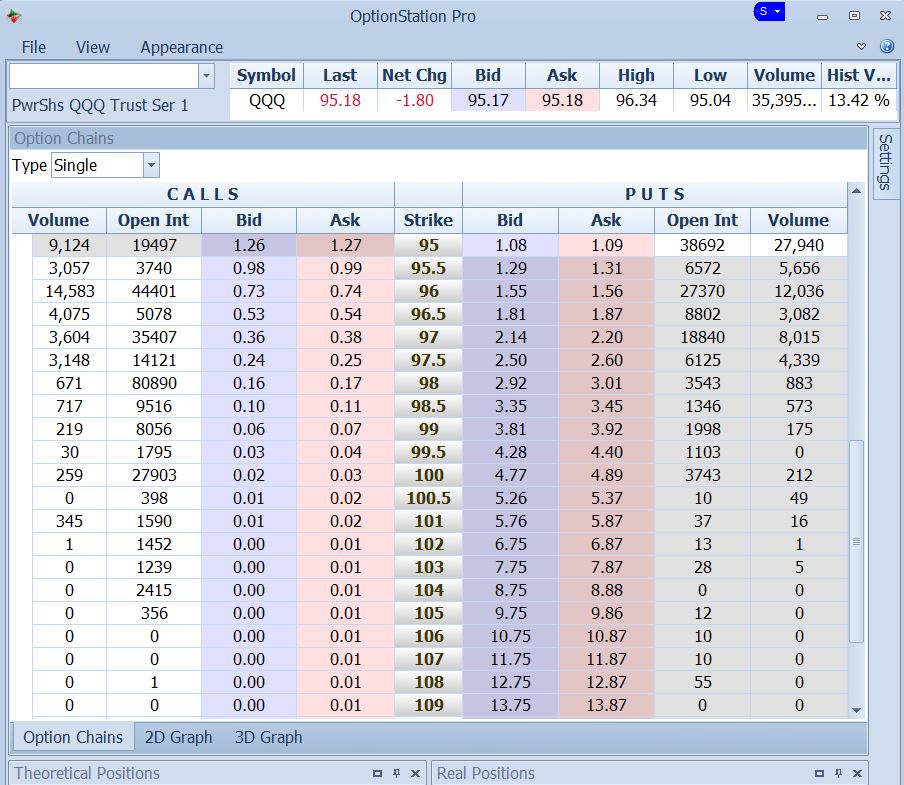

Figure 1 – QQQ August Option Chain

Above is the option chain for the exchange-traded fund QQQ. This is one of the most actively traded assets in existence, and its options likewise have a great deal of activity.

At this time, QQQ was trading around $95. The $95 strike price is at the top of the above option chain. For the $95 calls, the Bid is $1.26, and the Ask is $1.27. We could sell these options at the $1.26 Bid; or we could buy them at the $1.27 Ask. The bid-ask spread is as small as it can possibly be, at just one cent. Even at some distance away from the at-the-money strikes, all of the options have bid-ask spreads of just a few pennies.

Notice the columns labeled “Volume” and “Open Interest.” The quantities there are in the thousands or tens of thousands. Volume is the number of option contracts that have traded today. Open Interest is the total number of contracts in existence for the given strike price. The fact that these numbers are very large indicates a great deal of activity, presumably by many different traders. This explains the narrow spreads.

So for the QQQ, the answer to the question, “Who is on the other side of your trade?” could very well be – “another trader.”

Now contrast this with a different ETF at around the same price:

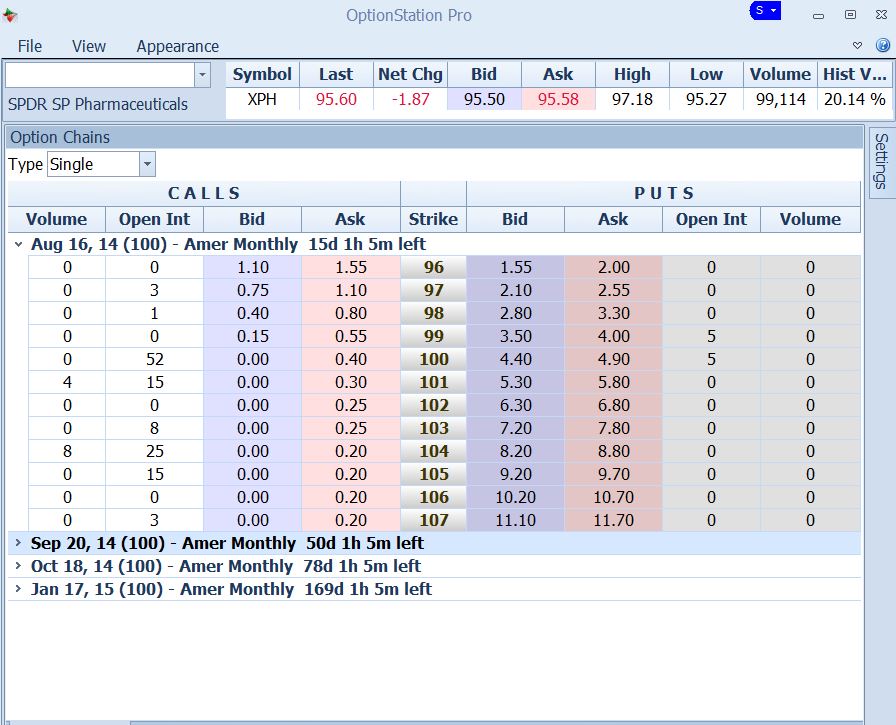

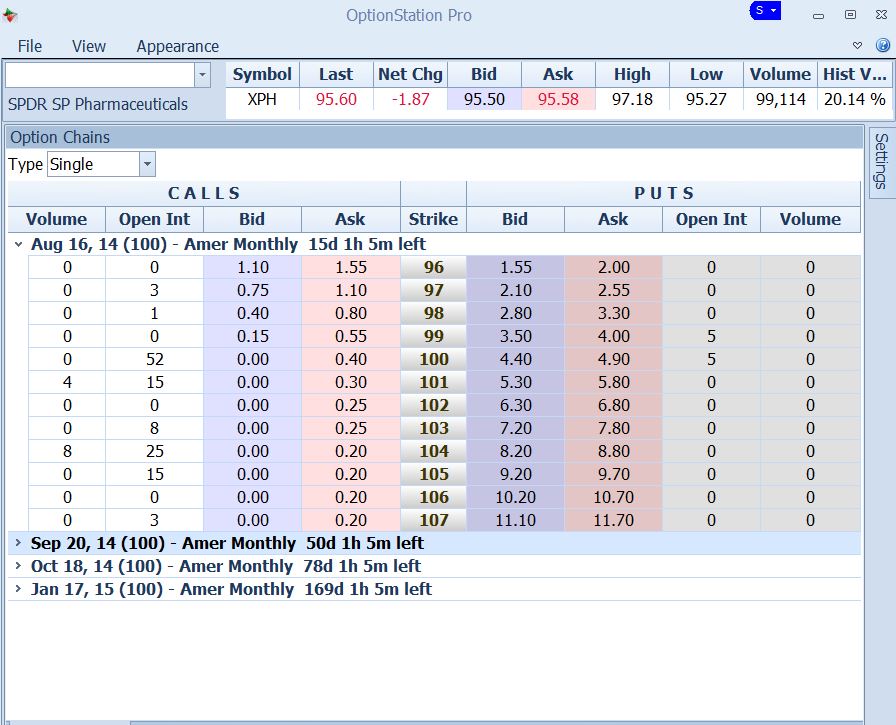

Figure 2 – XPH August Option Chain

Above is the option chain for the Pharmaceuticals ETF, whose symbol is XPH. It is trading at $95.60, about the same price as QQQ. But look at the bid-ask spread on the options. The $96 calls are Bid at $1.10, while the Ask is $1.55. Instead of one cent, that spread is $1.55 – $1.10 = $.45. This is a humongous 41% of the bid price.

We can see above that in stark contrast to QQQ, this ETF has very low numbers for Volume and Open Interest. The annual traders’ convention for these options could be held in a broom closet. With so few people participating, in most cases we would be dealing with the market makers, and there might be very few even of them.

So on this asset, the answer to the question, “Who is on the other side of your trade?” is almost certainly “a market maker.”

When the market maker is the only game in town, he will demand a large markup between his bid and ask prices. In part, this is because he must. With little turnover on these options he has to increase his profit per unit to make it make business sense for him. If there were many people trading these options, then he would have many more transactions. This both makes his business smoother and makes his hedging easier, so that he can afford to offer better spreads; and he is forced to do so by the competition from other traders.

So to put it in a nutshell:

Stick to assets whose options have a large amount of volume and open interest. Don’t be the pigeon in the only game in town.

Russ Allen can be contacted on this link: Russ Allen

The options market is made up of multiple exchanges. Each exchange hosts many options “market makers.” The market makers are broker/dealers, whose job is to buy options wholesale and sell them at retail. These dealers are always present in the market.

The market makers’ computer systems make sure that they have a bid price and an offered price in the market at all times for all the options they deal in. This is true whether any trades have taken place in each option or not.

Their presence explains why the option chain for each stock is fully populated. All the market makers are constantly transmitting their bid and ask prices to their exchanges.

The exchanges co-operate in a committee called the Option Price Reporting Authority (OPRA), which aggregates all the data and feeds it out to the public through data vendors. What we see on our option chains is the result of this aggregation and dissemination from OPRA.

This includes bids and offers from all of the option market makers, as well as from all other traders, including you. We see just one number as the “Bid” for the option and another for the “Ask.” But these are just the best (highest) bid and the best (lowest) ask price available among the many bids and asks from all the players.

All well and good as long as there are plenty of people competing for our business on whatever options we’re interested in. As long as that is true, the spread between the bid price and the ask price will be narrow. The competition from other traders will keep the market makers honest; if the market makers were to try to maintain a wide bid-ask spread, they would be undercut by the other players and that spread would narrow.

That is what happens with options that are widely traded. Below is an illustration:

Figure 1 – QQQ August Option Chain

Above is the option chain for the exchange-traded fund QQQ. This is one of the most actively traded assets in existence, and its options likewise have a great deal of activity.

At this time, QQQ was trading around $95. The $95 strike price is at the top of the above option chain. For the $95 calls, the Bid is $1.26, and the Ask is $1.27. We could sell these options at the $1.26 Bid; or we could buy them at the $1.27 Ask. The bid-ask spread is as small as it can possibly be, at just one cent. Even at some distance away from the at-the-money strikes, all of the options have bid-ask spreads of just a few pennies.

Notice the columns labeled “Volume” and “Open Interest.” The quantities there are in the thousands or tens of thousands. Volume is the number of option contracts that have traded today. Open Interest is the total number of contracts in existence for the given strike price. The fact that these numbers are very large indicates a great deal of activity, presumably by many different traders. This explains the narrow spreads.

So for the QQQ, the answer to the question, “Who is on the other side of your trade?” could very well be – “another trader.”

Now contrast this with a different ETF at around the same price:

Figure 2 – XPH August Option Chain

Above is the option chain for the Pharmaceuticals ETF, whose symbol is XPH. It is trading at $95.60, about the same price as QQQ. But look at the bid-ask spread on the options. The $96 calls are Bid at $1.10, while the Ask is $1.55. Instead of one cent, that spread is $1.55 – $1.10 = $.45. This is a humongous 41% of the bid price.

We can see above that in stark contrast to QQQ, this ETF has very low numbers for Volume and Open Interest. The annual traders’ convention for these options could be held in a broom closet. With so few people participating, in most cases we would be dealing with the market makers, and there might be very few even of them.

So on this asset, the answer to the question, “Who is on the other side of your trade?” is almost certainly “a market maker.”

When the market maker is the only game in town, he will demand a large markup between his bid and ask prices. In part, this is because he must. With little turnover on these options he has to increase his profit per unit to make it make business sense for him. If there were many people trading these options, then he would have many more transactions. This both makes his business smoother and makes his hedging easier, so that he can afford to offer better spreads; and he is forced to do so by the competition from other traders.

So to put it in a nutshell:

Stick to assets whose options have a large amount of volume and open interest. Don’t be the pigeon in the only game in town.

Russ Allen can be contacted on this link: Russ Allen

Last edited by a moderator: