Why is this a good time to invest in the U.S.? Believe it or not, but it may be because of the deficit! Amid all the hand ringing and gnashing of teeth by politicians of both political parties over growth of the federal budget deficit, evidence suggests that right now may be the best time in a decade to be saving and investing.

Revisiting the bursting of the bubble

To fully appreciate why now may be a good time to invest in U.S. stocks despite record high deficits, it would be time profitably spent to revisit the spring of 2000 just before the tax deadline. The government was running a record budget surplus for the third straight year, and the stock market was at an all time high. During the week leading up to April 15 indices started to unfold, (see table below). One theory offered at the time to explain this pattern was that over the weekend people were learning from their accountants that that they owed taxes to the IRS. Anyone hearing this news who owned stocks could of course sell off enough shares to meet their tax obligation. But what if too many people were doing exactly the same thing? See link:

http://www.greenspun.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg.tcl?msg_id=0038YZ

In this sense, the federal budget surplus, which was predicated on historically high tax revenues as a percentage of GDP, may have contributed to forcing taxpayers to cannibalize their invested savings to meet their tax liabilities.

Dark side of the budget surplus

The federal budget surplus, which had eluded policy makers for so long, was thought to be the Holy Grail of fiscal policy, but perhaps there was a dark side to it. When it comes right down to it, a budget surplus is simply evidence that taxpayers are being overcharged for services provided by the government. This begs the question of who is better qualified to allocate the surplus tax revenue, central planners in the government bureaucracy, or the millions of taxpayers who earned that revenue?

The prevailing wisdom of the late 1990s among Democrat and Republican politicians alike was that the surplus should be used to pay down government debt, which would get rid of it and supposedly free the government from having to pay interest in the future. However, this policy proved to be an illusion because it merely shifted the burden of the debt from the public sector onto the private sector. Investors owning Treasury notes and bonds who elected to sell their holdings back to the government would subsequently have to re-invest the cash proceeds in some other asset class. The difference on the margin was that investors who were displaced from the shrinking supply of treasury debt had no other option but to descend the credit ladder and re-allocate their capital into the expanded supply of private sector debt and equity IPO's that filled the void. In hindsight it is easy to see that many of these investments were not properly priced to reflect the

credit risk.

Deficits as far as the eye can see

Rightly or wrongly, the fiscal policies that prevailed during the Reagan administration in the 1980s are often criticized for creating "deficits as far as the eye could see", but the reality of these "chronic" deficits somehow did not get in the way of the

S&P 500 index more than doubling during Reagan's two terms in office; this, notwithstanding the 1987 stock market crash. Of course, this doesn't necessarily mean that the deficits of the 1980s were responsible for the stock market advances in the 1980s, but it might be worth noting that the crash of '87 occurred during the year when the federal budget deficit declined from 5.03% to 3.22% of GDP. Note also, that the top marginal tax on long term capital gains held for more than one year was raised to 28% from 20% in 1986 as part of the tax reform act passed in that that year.

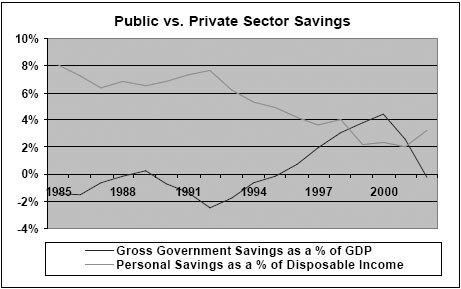

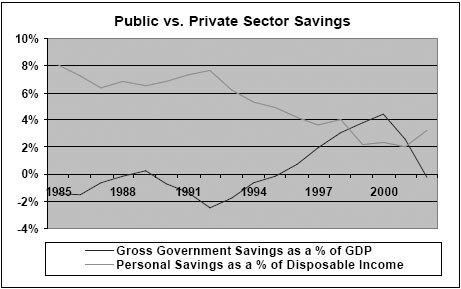

Today we find that the budget surpluses of a few years ago are gone, and replaced once again with large deficits attributable to a sharp decline in tax revenues from the recession, big spending increases associated with homeland defense and other pork projects, and tax cuts. Roughly $100 billion of the $374 billion federal budget deficit for fiscal year 2003 was attributable to the two rounds of tax cuts that have gone into effect over the past three years. In connection with this, the chart in federal, state and local savings as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with private savings as percentage of personal disposable income. The chart clearly illustrates that during the years when the government was running a budget surplus, (i.e. government savings), individuals for some reason found in increasingly difficult to save. In other words, the chart illustrates an inverse relationship between the personal savings rate and the government savings rate. However, the chart also shows that with the return of government budget deficits, the personal savings rate has turned around again and begun to climb. Why the increase in savings?

Could it be that people are saving more because they are being taxed less? Logically, this makes sense because people will have more ability to save and invest if they are having less in taxes withheld from their paychecks. The positive impact for investing can not be overstated assuming that the tax cuts are made permanent, because it suggests that going forward there will a growing supply of investment dollars available to be allocated into stocks, bonds and other assets classes.

Figure 1

Source data: Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.doc.gov/)

Chart design: Beacon Hill Institute

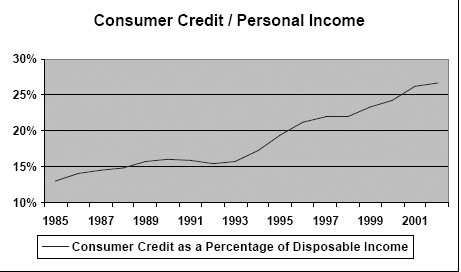

An alternative explanation offers the absurd rationale argued by some economists who claim that people save more after a tax cut because they believe they will be taxed more in the future, and so they want to put aside savings for that purpose. But this makes about as much sense as saying that people saved less during the years when the government was running a budget surplus because they figured they could rack up consumer debt and spend with impunity because future tax cuts would allow them to pay down their credit card balances. Government tax receipts climbed to a post WWII high of 20.85% of GDP in 2001. This suggests that despite making record net tax payments to the government, individuals continued on a consumer spending binge by going deeper into debt. The chart in Figure 2, which graphs a ratio of total consumer credit to disposable personal income, lends support to this view.

Of course, an increase in private sector borrowing would translate into a net decline in savings. But, why would a government budget surplus cause private borrowing to go up? The answer to that question may not be intuitively obvious, but one thing is clear; consumer spending continued at a robust pace even as total consumer credit, as tracked by the Federal Reserve, consisting roughly two thirds of auto loans and one third revolving credit card debt, started to pitch sharply higher in the mid to late 1990s. It will be interesting to see as the data becomes available for fiscal year 2003, if the ratio of consumer credit to personal income starts to trend down again. This would be consistent with the recent upturn in the savings rate seen in Figure 1.

Figure 2

Source data: Federal Reserve (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/hist), Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.doc.gov).

So, if past is prelude to the future, and the latest government forecasts of a federal budget deficit approaching $525 billion for 2004 fiscal year are borne out, it implies that consumer debt loads will ease and private sector savings will continue to rise. By extension, this means that the markets will receive fresh infusions of capital to be invested in the year ahead as more investors feel comfortable enough to go back into the water seeking the higher after tax return on capital from the new and improved low tax rate environment.

Revisiting the bursting of the bubble

To fully appreciate why now may be a good time to invest in U.S. stocks despite record high deficits, it would be time profitably spent to revisit the spring of 2000 just before the tax deadline. The government was running a record budget surplus for the third straight year, and the stock market was at an all time high. During the week leading up to April 15 indices started to unfold, (see table below). One theory offered at the time to explain this pattern was that over the weekend people were learning from their accountants that that they owed taxes to the IRS. Anyone hearing this news who owned stocks could of course sell off enough shares to meet their tax obligation. But what if too many people were doing exactly the same thing? See link:

http://www.greenspun.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg.tcl?msg_id=0038YZ

In this sense, the federal budget surplus, which was predicated on historically high tax revenues as a percentage of GDP, may have contributed to forcing taxpayers to cannibalize their invested savings to meet their tax liabilities.

Dark side of the budget surplus

The federal budget surplus, which had eluded policy makers for so long, was thought to be the Holy Grail of fiscal policy, but perhaps there was a dark side to it. When it comes right down to it, a budget surplus is simply evidence that taxpayers are being overcharged for services provided by the government. This begs the question of who is better qualified to allocate the surplus tax revenue, central planners in the government bureaucracy, or the millions of taxpayers who earned that revenue?

The prevailing wisdom of the late 1990s among Democrat and Republican politicians alike was that the surplus should be used to pay down government debt, which would get rid of it and supposedly free the government from having to pay interest in the future. However, this policy proved to be an illusion because it merely shifted the burden of the debt from the public sector onto the private sector. Investors owning Treasury notes and bonds who elected to sell their holdings back to the government would subsequently have to re-invest the cash proceeds in some other asset class. The difference on the margin was that investors who were displaced from the shrinking supply of treasury debt had no other option but to descend the credit ladder and re-allocate their capital into the expanded supply of private sector debt and equity IPO's that filled the void. In hindsight it is easy to see that many of these investments were not properly priced to reflect the

credit risk.

Deficits as far as the eye can see

Rightly or wrongly, the fiscal policies that prevailed during the Reagan administration in the 1980s are often criticized for creating "deficits as far as the eye could see", but the reality of these "chronic" deficits somehow did not get in the way of the

S&P 500 index more than doubling during Reagan's two terms in office; this, notwithstanding the 1987 stock market crash. Of course, this doesn't necessarily mean that the deficits of the 1980s were responsible for the stock market advances in the 1980s, but it might be worth noting that the crash of '87 occurred during the year when the federal budget deficit declined from 5.03% to 3.22% of GDP. Note also, that the top marginal tax on long term capital gains held for more than one year was raised to 28% from 20% in 1986 as part of the tax reform act passed in that that year.

Today we find that the budget surpluses of a few years ago are gone, and replaced once again with large deficits attributable to a sharp decline in tax revenues from the recession, big spending increases associated with homeland defense and other pork projects, and tax cuts. Roughly $100 billion of the $374 billion federal budget deficit for fiscal year 2003 was attributable to the two rounds of tax cuts that have gone into effect over the past three years. In connection with this, the chart in federal, state and local savings as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) with private savings as percentage of personal disposable income. The chart clearly illustrates that during the years when the government was running a budget surplus, (i.e. government savings), individuals for some reason found in increasingly difficult to save. In other words, the chart illustrates an inverse relationship between the personal savings rate and the government savings rate. However, the chart also shows that with the return of government budget deficits, the personal savings rate has turned around again and begun to climb. Why the increase in savings?

Could it be that people are saving more because they are being taxed less? Logically, this makes sense because people will have more ability to save and invest if they are having less in taxes withheld from their paychecks. The positive impact for investing can not be overstated assuming that the tax cuts are made permanent, because it suggests that going forward there will a growing supply of investment dollars available to be allocated into stocks, bonds and other assets classes.

Figure 1

Source data: Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.doc.gov/)

Chart design: Beacon Hill Institute

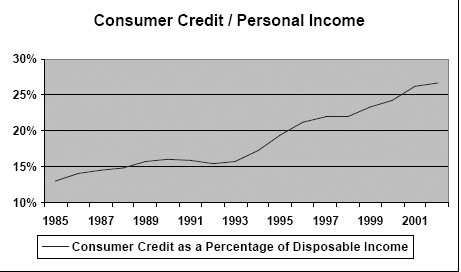

An alternative explanation offers the absurd rationale argued by some economists who claim that people save more after a tax cut because they believe they will be taxed more in the future, and so they want to put aside savings for that purpose. But this makes about as much sense as saying that people saved less during the years when the government was running a budget surplus because they figured they could rack up consumer debt and spend with impunity because future tax cuts would allow them to pay down their credit card balances. Government tax receipts climbed to a post WWII high of 20.85% of GDP in 2001. This suggests that despite making record net tax payments to the government, individuals continued on a consumer spending binge by going deeper into debt. The chart in Figure 2, which graphs a ratio of total consumer credit to disposable personal income, lends support to this view.

Of course, an increase in private sector borrowing would translate into a net decline in savings. But, why would a government budget surplus cause private borrowing to go up? The answer to that question may not be intuitively obvious, but one thing is clear; consumer spending continued at a robust pace even as total consumer credit, as tracked by the Federal Reserve, consisting roughly two thirds of auto loans and one third revolving credit card debt, started to pitch sharply higher in the mid to late 1990s. It will be interesting to see as the data becomes available for fiscal year 2003, if the ratio of consumer credit to personal income starts to trend down again. This would be consistent with the recent upturn in the savings rate seen in Figure 1.

Figure 2

Source data: Federal Reserve (http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/hist), Bureau of Economic Analysis (http://www.bea.doc.gov).

So, if past is prelude to the future, and the latest government forecasts of a federal budget deficit approaching $525 billion for 2004 fiscal year are borne out, it implies that consumer debt loads will ease and private sector savings will continue to rise. By extension, this means that the markets will receive fresh infusions of capital to be invested in the year ahead as more investors feel comfortable enough to go back into the water seeking the higher after tax return on capital from the new and improved low tax rate environment.

Last edited by a moderator: