You’re a trader, right, not a shopkeeper and there can’t possibly be any common ground between the two can there? Just a minute, though, both are trying to make a profit from the transactions they undertake and both are concerned about their bottom line and their overall and continued profitability. In short, both are in business.

As a trader it is quite likely that your Trading Plan will concentrate its focus on how you will approach individual trades. It will probably have quite a lot about how and when you will enter a trade, rather less about how you will guard against excessive loss and less again about how and when you will take your gains. Your bottom line probably won’t rate much of a mention at all. A Business Plan, however, will concentrate its focus on the bottom line and recognise that individual transactions are important only in respect of the contribution they must make to keep that bottom line healthy.

This article asks you to think of your trading as an overall business and demonstrates how you might gear your approach to your trades with that in mind.

So, let’s think like our shopkeeper for a moment, who might talk in this way about his Business Plan:

“I buy my widgets at £10 each and I aim to make a return on my outlay in excess of 25% to ensure healthy and continued profitability overall. I stock up with a thousand widgets each month and sell them for £20 each but, at that price, past experience tells me that I will only sell 40% of my stock. However, my supplier guarantees me £8 for those I return.”

His monthly account looks like this:

400 @ £10 profit = £4,000

600 @ £2 loss = - £1,200

Net profit = £2,800 = 28% return on initial £10,000 outlay.

I’m sure you will have noted that restricting his losses on the widgets he can’t sell is absolutely crucial to that result.

But you’re not a shopkeeper, you’re a trader, so let’s now think like one and describe your business in trading terms:

“I aim to grow my trading account of £10,000 by 20% overall year on year. I am not prepared to lose more than £200 on any trade and look to gain at least £350 from those that are successful. With these criteria, I know from past experience that only 40% of my trades are likely to be successful. I make 100 trades each year.”

Your yearly account looks like this:

40 @ £ 350 profit = £14,000

60 @ £ 200 loss = - £12,000

Net profit = £2,000 = 20% return on initial £10,000 account.

That’s nice and easy, then, we’ll all be millionaires in no time. Unfortunately, as we all know, it’s quite the reverse of easy and it’s all very well to describe your business like that but, in truth, it is more a statement of intent to work with rather than one that contains much certainty in practice. It does, however, mean that you might approach your trading in a slightly different way and I’ll move on to that now.

The elements of a trade

The three important questions to consider when you are planning a trade are:

entry - when and where will I buy/sell

risk - how much will I lose if it goes wrong

exit - when and where will I sell/buy to realise gains

It’s quite likely, particularly if you are inexperienced, that you will consider those questions in that order and in that order of importance. From a business perspective it’s slightly different.

When a potential trade entry beckons the first thing you must look at is your risk because this is the only thing you can be certain about from the outset, barring isolated disaster events. You are in control of it and it is essential to your business that you exercise that control unfailingly. Your control comes from a combination of stop loss exit and position size (see later). You will remember from our shopkeeper that limiting his losses was the crucial factor in his overall profitability.

Secondly, you must look to your exit in respect of where you will realise your gains. For this you will set a target level. You cannot be in anyway certain that price will reach this target, of course, but you can make a reasonable assumption based on your experience of the particular strategy or method that you use.

Lastly, you turn back to your entry because it is only when you have considered your risk (certain) and your exit target (potential only) that you are in a position to judge whether a trade at the entry level you have in mind is a worthwhile proposition or not.

To sum this up here is an example of how a trader might look at a potential trade.

The retracement trader: the outline plan

First, a bit about this trader and his strategy in order to see his planned trade in context.

His strategy is to capture potential trend continuation after retracement. He assumes that price will at least challenge the high/low point of the main trend and this is where he plans to place his target. He will assume he will be wrong if price comes back to the low/high point of the retracement and this is where he plans to place his stoploss.

From the business perspective he also knows, from his past experience of the proportion of wins he has achieved with such trades, that if he achieves 1.5:1 reward to risk on winning trades his account will grow satisfactorily. Accordingly, he will not take a trade unless his planned target gives more than 1.5:1. When he takes a trade he will protect the 1.5:1 level and move his stoploss to it as soon as it is passed.

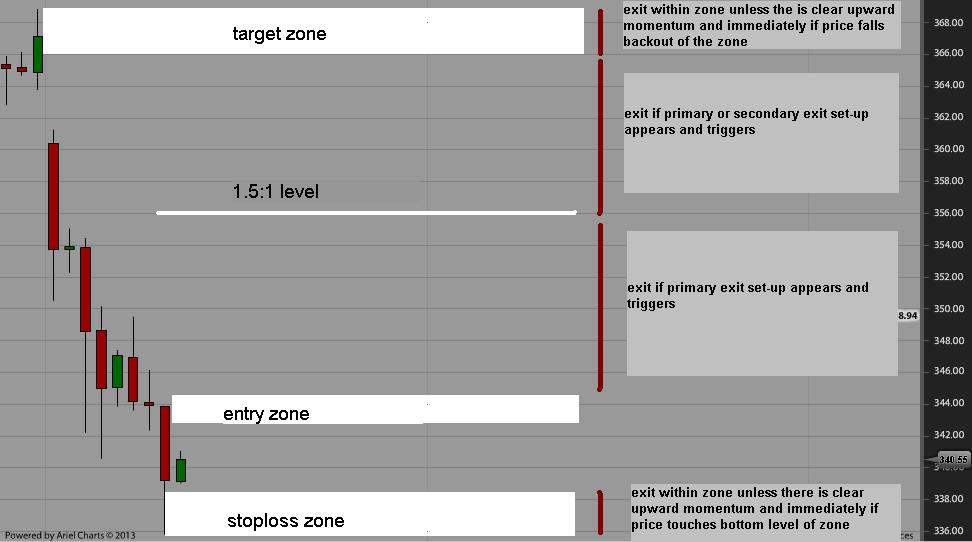

Here’s how that outline plan looks drawn in on a chart:

Fig 1

The retracement trader: the trading plan

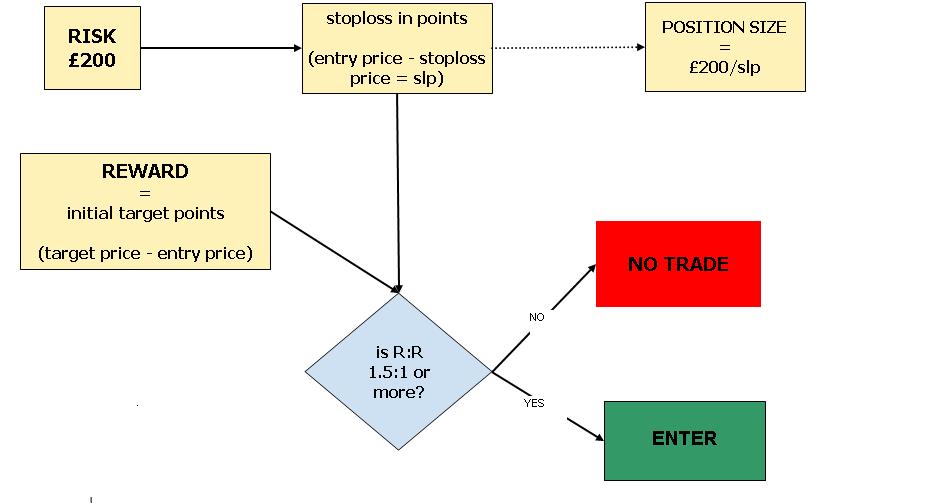

From the outline plan this is clearly a trade that our trader will be willing to take since the potential target is well above his minimum business requirement level of 1.5:1 reward to risk. He now marks up his chart with the important zones he will use and I have included a brief description of his tactics to give you some idea of how he will go about managing his trade. All he needs now is for price to come to his entry zone and he will want to see some momentum behind it if it does.

Fig 2

This sort of thing is probably quite familiar to you and you will have your own view as to the merits, or otherwise, of his basic trade strategy and his management of it. However, this is not about putting forward any particular strategy, but about indicating how it is influenced by his overall business thinking.

Firstly, he is reluctant to exit before his minimum requirement of 1.5:1 reward to risk is reached and he will only do so if there are really clear signs of danger. He has a primary exit set-up to use for this.

Secondly, once price is clear of his minimum requirement level (and he has re-set his stoploss to ensure it), he regards anything more as a bonus so far as his overall business is concerned. He is, therefore, much less reluctant to exit and will use both his primary and a secondary exit set-up to close the trade.

Thirdly, if price reaches his target level he will close unless there is really strong momentum to carry it further. He has, after all, got what he planned which is considerably more than he needs and he sees no point in hanging around for more without extremely good reason, particularly since he knows that the risk of reversal at this point is quite high.

Lastly, if price does not move as he expects after entry and heads instead towards his stoploss he is reluctant to live in hope that it will turn around and he will not wait to be stopped out - at the bottom level of his stoploss zone -unless he sees extremely good reasons to hold on.

Perhaps all this makes it sound as though our trader’s reasoning will be spot on or that he is a fortune teller who can foresee the future. There is not such a trader. All trading is about making assumptions based on experience of what has happened in similar circumstances in the past. Those assumptions may be right or they may be wrong and from the business perspective the aim is to gain the necessary advantage when they are right and limit the damage when they are not.

Is a trade worth taking?

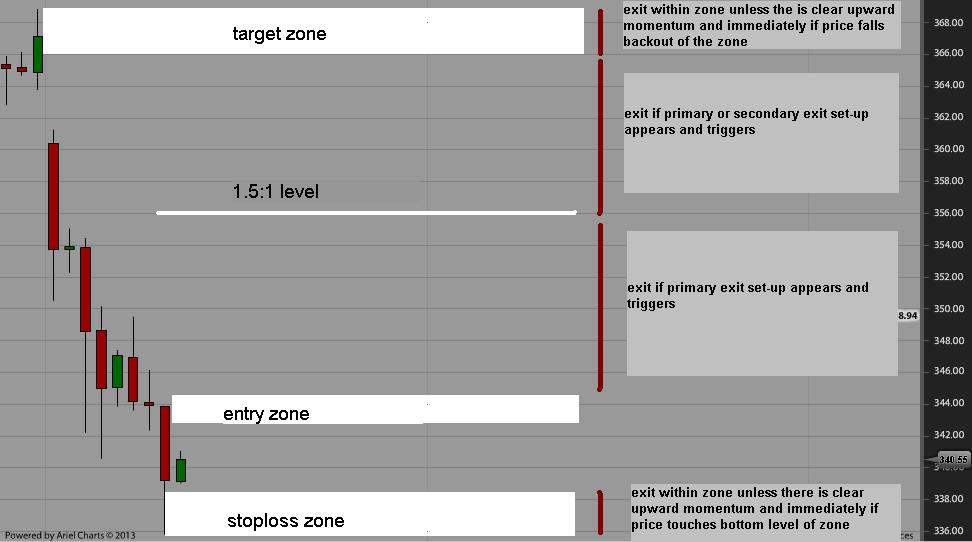

Earlier on in the article I talked about risk and controlling it by a combination of stoploss level and position size. The following flow chart starts by setting the risk as a fixed £ sum - in this case £200 as I used earlier - which then establishes your position size in terms of £ per point. You may, however, work with a fixed position size and in this case you go backwards from there to establish the £ amount at risk.

The flow chart also features the 1.5:1 reward to risk ratio used in our trader example. It is not a figure set in stone for all to follow and is only a figure applicable to that trader, his win rate and the growth he wishes to see in his account. Yours may well be different.

To calculate you own you will need a good number of trades under your belt to establish your win rate and your average reward to risk return on winning trades (your losing trades must have been rigidly controlled, of course). If that is giving you just on the minimum amount of account growth that you consider acceptable - and it is wise to be very conservative in that consideration - then your average reward to risk is probably the one to start with. Better than that minimum growth and you can scale it down. Worse and you can scale it up, but be careful of going too far lest the figure you finish up with is ludicrously unobtainable for the sort of trades you make.

If your account is decreasing over time then playing about with these figures is unlikely to improve matters unless the losses have accrued from bad risk control with sloppy control of your losing trades. Even then, you must put that right first. Otherwise you must first re-visit your strategy and tighten it up, or move on to something different.

Fig 3

A final word

I hope this article has given you something to think about so far as your own trading is concerned. Even if you remain unconvinced by an overall business approach I hope, too, that you will take away two important things.

The first is crucial to your success and it is to rigidly control and restrict your losses. It’s human nature not to like being wrong and taking a loss and the temptation to wait for price to come back and save your bacon is great. All too often price does just that but, on the occasion that it doesn’t, it will just get worse and worse until you have unravelled many weeks and more of hard fought gains before you eventually cry uncle. Failure to properly control your losses is the main reason why so many are unsuccessful at their trading and why so much is written about its importance.

The second is the importance of exits. Most trading literature you read about a multitude of strategies and methods concentrates on entries but, although a good entry is helpful, you make your money through your exits. It’s exits that move your account and they deserve your concentrated attention accordingly.

Good trading.

As a trader it is quite likely that your Trading Plan will concentrate its focus on how you will approach individual trades. It will probably have quite a lot about how and when you will enter a trade, rather less about how you will guard against excessive loss and less again about how and when you will take your gains. Your bottom line probably won’t rate much of a mention at all. A Business Plan, however, will concentrate its focus on the bottom line and recognise that individual transactions are important only in respect of the contribution they must make to keep that bottom line healthy.

This article asks you to think of your trading as an overall business and demonstrates how you might gear your approach to your trades with that in mind.

So, let’s think like our shopkeeper for a moment, who might talk in this way about his Business Plan:

“I buy my widgets at £10 each and I aim to make a return on my outlay in excess of 25% to ensure healthy and continued profitability overall. I stock up with a thousand widgets each month and sell them for £20 each but, at that price, past experience tells me that I will only sell 40% of my stock. However, my supplier guarantees me £8 for those I return.”

His monthly account looks like this:

400 @ £10 profit = £4,000

600 @ £2 loss = - £1,200

Net profit = £2,800 = 28% return on initial £10,000 outlay.

I’m sure you will have noted that restricting his losses on the widgets he can’t sell is absolutely crucial to that result.

But you’re not a shopkeeper, you’re a trader, so let’s now think like one and describe your business in trading terms:

“I aim to grow my trading account of £10,000 by 20% overall year on year. I am not prepared to lose more than £200 on any trade and look to gain at least £350 from those that are successful. With these criteria, I know from past experience that only 40% of my trades are likely to be successful. I make 100 trades each year.”

Your yearly account looks like this:

40 @ £ 350 profit = £14,000

60 @ £ 200 loss = - £12,000

Net profit = £2,000 = 20% return on initial £10,000 account.

That’s nice and easy, then, we’ll all be millionaires in no time. Unfortunately, as we all know, it’s quite the reverse of easy and it’s all very well to describe your business like that but, in truth, it is more a statement of intent to work with rather than one that contains much certainty in practice. It does, however, mean that you might approach your trading in a slightly different way and I’ll move on to that now.

The elements of a trade

The three important questions to consider when you are planning a trade are:

entry - when and where will I buy/sell

risk - how much will I lose if it goes wrong

exit - when and where will I sell/buy to realise gains

It’s quite likely, particularly if you are inexperienced, that you will consider those questions in that order and in that order of importance. From a business perspective it’s slightly different.

When a potential trade entry beckons the first thing you must look at is your risk because this is the only thing you can be certain about from the outset, barring isolated disaster events. You are in control of it and it is essential to your business that you exercise that control unfailingly. Your control comes from a combination of stop loss exit and position size (see later). You will remember from our shopkeeper that limiting his losses was the crucial factor in his overall profitability.

Secondly, you must look to your exit in respect of where you will realise your gains. For this you will set a target level. You cannot be in anyway certain that price will reach this target, of course, but you can make a reasonable assumption based on your experience of the particular strategy or method that you use.

Lastly, you turn back to your entry because it is only when you have considered your risk (certain) and your exit target (potential only) that you are in a position to judge whether a trade at the entry level you have in mind is a worthwhile proposition or not.

To sum this up here is an example of how a trader might look at a potential trade.

The retracement trader: the outline plan

First, a bit about this trader and his strategy in order to see his planned trade in context.

His strategy is to capture potential trend continuation after retracement. He assumes that price will at least challenge the high/low point of the main trend and this is where he plans to place his target. He will assume he will be wrong if price comes back to the low/high point of the retracement and this is where he plans to place his stoploss.

From the business perspective he also knows, from his past experience of the proportion of wins he has achieved with such trades, that if he achieves 1.5:1 reward to risk on winning trades his account will grow satisfactorily. Accordingly, he will not take a trade unless his planned target gives more than 1.5:1. When he takes a trade he will protect the 1.5:1 level and move his stoploss to it as soon as it is passed.

Here’s how that outline plan looks drawn in on a chart:

Fig 1

The retracement trader: the trading plan

From the outline plan this is clearly a trade that our trader will be willing to take since the potential target is well above his minimum business requirement level of 1.5:1 reward to risk. He now marks up his chart with the important zones he will use and I have included a brief description of his tactics to give you some idea of how he will go about managing his trade. All he needs now is for price to come to his entry zone and he will want to see some momentum behind it if it does.

Fig 2

This sort of thing is probably quite familiar to you and you will have your own view as to the merits, or otherwise, of his basic trade strategy and his management of it. However, this is not about putting forward any particular strategy, but about indicating how it is influenced by his overall business thinking.

Firstly, he is reluctant to exit before his minimum requirement of 1.5:1 reward to risk is reached and he will only do so if there are really clear signs of danger. He has a primary exit set-up to use for this.

Secondly, once price is clear of his minimum requirement level (and he has re-set his stoploss to ensure it), he regards anything more as a bonus so far as his overall business is concerned. He is, therefore, much less reluctant to exit and will use both his primary and a secondary exit set-up to close the trade.

Thirdly, if price reaches his target level he will close unless there is really strong momentum to carry it further. He has, after all, got what he planned which is considerably more than he needs and he sees no point in hanging around for more without extremely good reason, particularly since he knows that the risk of reversal at this point is quite high.

Lastly, if price does not move as he expects after entry and heads instead towards his stoploss he is reluctant to live in hope that it will turn around and he will not wait to be stopped out - at the bottom level of his stoploss zone -unless he sees extremely good reasons to hold on.

Perhaps all this makes it sound as though our trader’s reasoning will be spot on or that he is a fortune teller who can foresee the future. There is not such a trader. All trading is about making assumptions based on experience of what has happened in similar circumstances in the past. Those assumptions may be right or they may be wrong and from the business perspective the aim is to gain the necessary advantage when they are right and limit the damage when they are not.

Is a trade worth taking?

Earlier on in the article I talked about risk and controlling it by a combination of stoploss level and position size. The following flow chart starts by setting the risk as a fixed £ sum - in this case £200 as I used earlier - which then establishes your position size in terms of £ per point. You may, however, work with a fixed position size and in this case you go backwards from there to establish the £ amount at risk.

The flow chart also features the 1.5:1 reward to risk ratio used in our trader example. It is not a figure set in stone for all to follow and is only a figure applicable to that trader, his win rate and the growth he wishes to see in his account. Yours may well be different.

To calculate you own you will need a good number of trades under your belt to establish your win rate and your average reward to risk return on winning trades (your losing trades must have been rigidly controlled, of course). If that is giving you just on the minimum amount of account growth that you consider acceptable - and it is wise to be very conservative in that consideration - then your average reward to risk is probably the one to start with. Better than that minimum growth and you can scale it down. Worse and you can scale it up, but be careful of going too far lest the figure you finish up with is ludicrously unobtainable for the sort of trades you make.

If your account is decreasing over time then playing about with these figures is unlikely to improve matters unless the losses have accrued from bad risk control with sloppy control of your losing trades. Even then, you must put that right first. Otherwise you must first re-visit your strategy and tighten it up, or move on to something different.

Fig 3

A final word

I hope this article has given you something to think about so far as your own trading is concerned. Even if you remain unconvinced by an overall business approach I hope, too, that you will take away two important things.

The first is crucial to your success and it is to rigidly control and restrict your losses. It’s human nature not to like being wrong and taking a loss and the temptation to wait for price to come back and save your bacon is great. All too often price does just that but, on the occasion that it doesn’t, it will just get worse and worse until you have unravelled many weeks and more of hard fought gains before you eventually cry uncle. Failure to properly control your losses is the main reason why so many are unsuccessful at their trading and why so much is written about its importance.

The second is the importance of exits. Most trading literature you read about a multitude of strategies and methods concentrates on entries but, although a good entry is helpful, you make your money through your exits. It’s exits that move your account and they deserve your concentrated attention accordingly.

Good trading.

Last edited by a moderator: